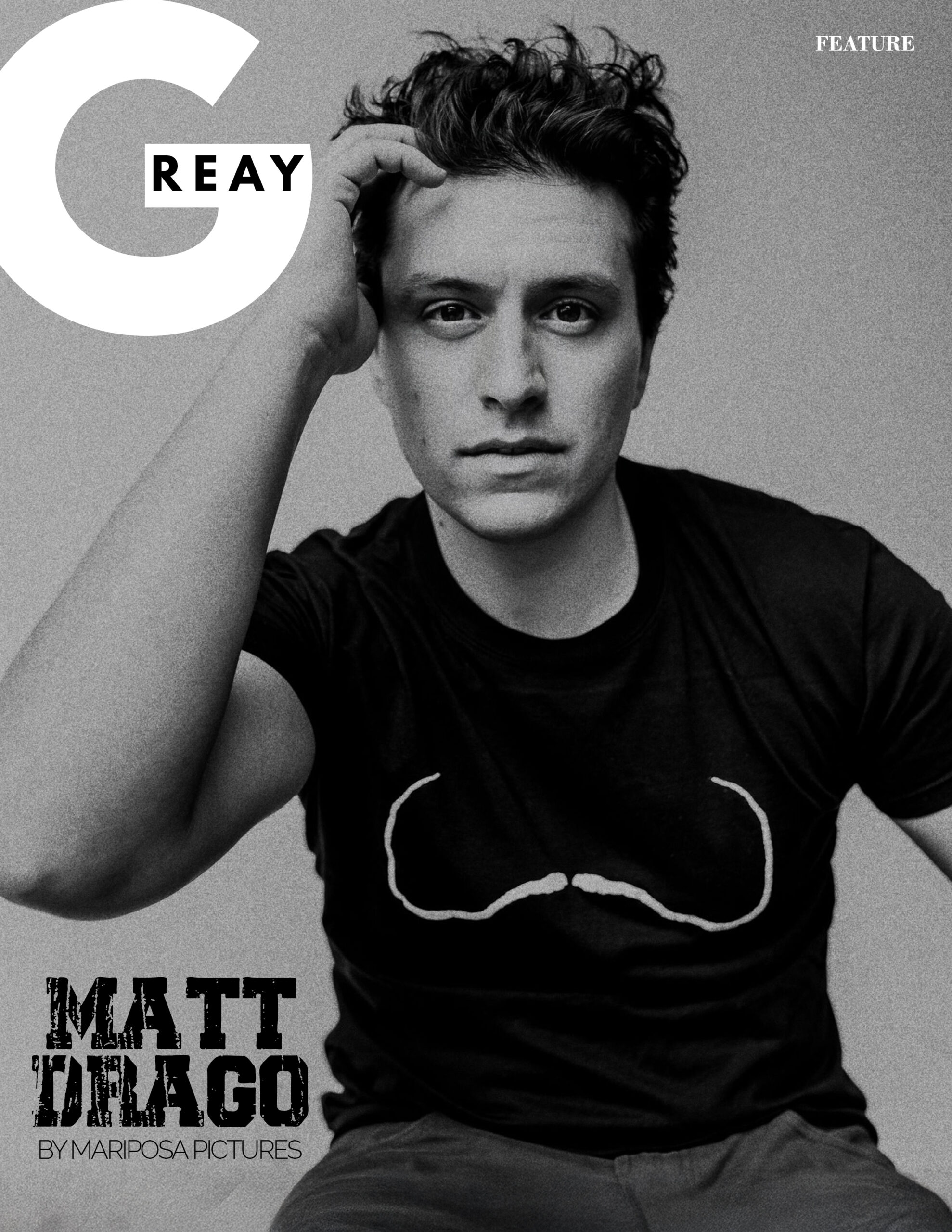

Matt Drago’s Way of the Warrior: Discipline On and Off Screen

By Kyra Greene

In an industry addicted to speed, visibility, and the illusion of overnight success, he is a reminder of what artistry looks like when it’s built slowly—brick by brick, breath by breath. His path has never been about shortcuts or spectacle. Instead, it has been shaped by discipline handed down in a dojo, late-night shifts in New York bars, self-funded training sessions, and a spiritual curiosity that refuses to settle for performance without meaning. In Somewhere in Montana, his breakout turn as Fabian marks not just a career milestone but a convergence point—where martial arts, emotional honesty, and a lifelong study of presence finally meet. The result is a performance that feels carved from truth, shaped by silence, and carried by a body that knows how to tell the story before the words ever arrive.

1. You’ve trained in both acting and martial arts — two worlds that demand discipline, precision, and presence. How do those practices inform each other when you’re stepping into a character like Fabian in Somewhere in Montana?

Training in both acting and martial arts taught me a shared language: discipline, precision, and presence. Growing up in a dojo with my father as my Sensei, I was immersed early in the discipline and philosophy of martial arts. This foundation shaped not only my physicality but my approach to life and art. Martial arts demands a physical clarity — how you hold your body, how you move through space, how breath and timing control intention. My acting training, which included Suzuki training, provided a powerful bridge between these two practices, merging physical discipline with emotional depth. When I become Fabian in Somewhere in Montana, I use martial training to root the character physically — the way he carries weight, reacts under pressure, and occupies a room — and acting to translate those physical choices into inner life. The result is a performance where movement and emotion feel inseparable and authentic.

Somewhere in Montana explores two men forced to confront their differences. What personal truths did you uncover in yourself while inhabiting that emotional space?

Stepping into the emotional landscape of Somewhere in Montana meant peeling back layers of masculinity, silence, and vulnerability. Inhabiting that space, I was struck by how often we carry unspoken grief—how much of ourselves we bury beneath pride, fear, or the need to appear strong. The characters’ journey forced me to confront my own assumptions about connection: how easy it is to misread someone’s silence as indifference, when it might actually be pain.

What I uncovered was a truth about reconciliation—not just with others, but with the parts of ourselves we’ve long ignored. The film reminded me that healing doesn’t always come through grand gestures. Sometimes, it’s in the quiet moments: a shared glance, a reluctant apology, or the simple act of staying when it would be easier to walk away.

Many emerging actors chase visibility; you’ve emphasized mastery — studying in New York, building from the ground up. What has “patience” meant to you in a culture obsessed with immediacy?

Patience, to me, has never meant waiting. It’s meant working — quietly, consistently, often without applause. Along the way, I’ve been fortunate to learn from incredible mentors who shaped my craft deeply. My time in Terry Schreiber’s scene study class was transformative, teaching me the nuances of presence and truth on stage. Working with audition guru Michael Lavine sharpened my approach to the business side of performance, while vocal master Ron Shetler helped me find and refine my authentic voice. In a culture that rewards the loudest voice in the room or the most viral moment, choosing to build something slowly can feel almost rebellious. But I’ve always believed that the deeper the roots, the stronger the tree.

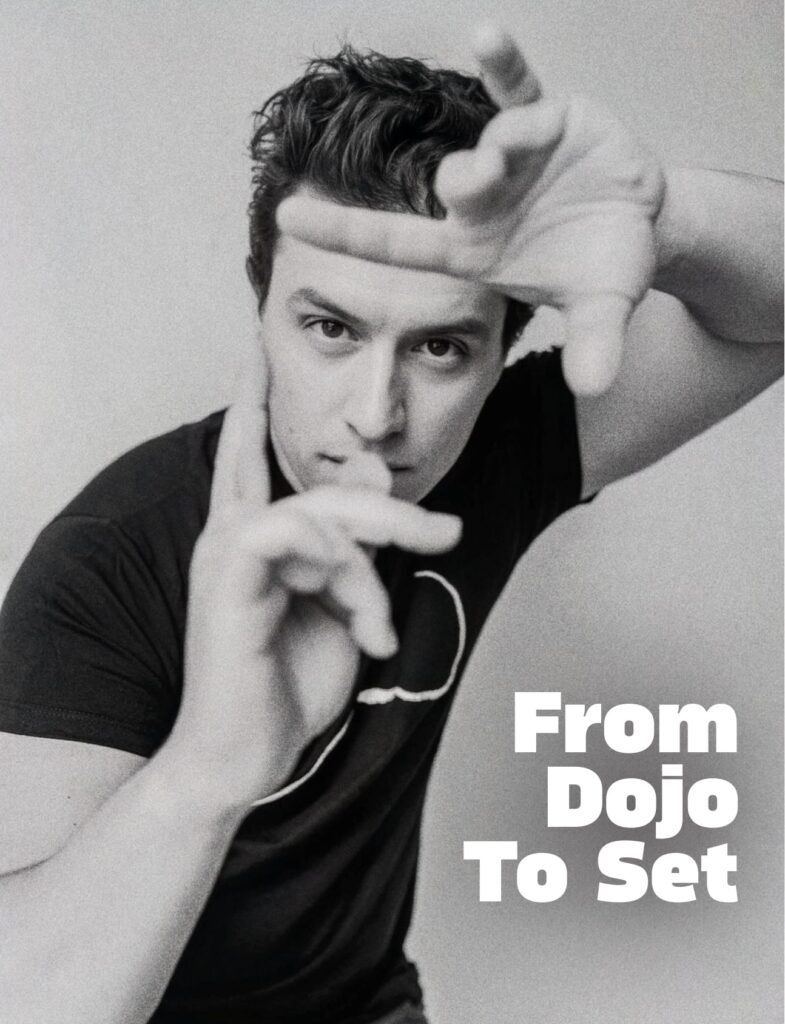

On-screen, you move with a physical awareness that feels almost choreographed. Do you approach performance through the body first — or through the psychology of the character?

For me, it’s never strictly one or the other. Sometimes the psychology of the character leads the way: I’ll dive into their emotional world, their motivations, their fears, and let that internal landscape shape how they move, how they hold themselves, how they react physically to the world around them. Other times, it’s the body that unlocks the character. I might find a posture, a rhythm, a gesture — and suddenly the emotional truth clicks into place. Especially in roles that are more stylized or physically demanding, movement becomes the gateway to understanding who this person is. Ultimately, it’s a dance between the two. The psychology informs the physicality, and the physicality deepens the psychology. I try to stay open to whichever path reveals the character most truthfully, and often it’s in rehearsal — in the doing — that the balance finds itself.

You’ve mentioned wanting to tell stories that carry emotional and spiritual depth. What does “faith” mean to you today — not necessarily religion, but belief — in art, in yourself, in the process?

My process as an actor is deeply rooted in the use of backstory and the many methodologies I’ve learned along the way. By weaving together techniques from various acting traditions, I create a unique approach that allows me to fully inhabit my characters. The backstory serves as a foundation, giving depth and motivation to every choice I make on stage or screen, while the diverse methodologies provide tools to explore and express the emotional truth of each role. Faith in this process is essential. It sustains me through the uncertainties and challenges of acting, reminding me that the work is about commitment rather than certainty. Trusting in the process — in the backstory, the methods, and my own instincts — allows me to stay present and open, knowing that authenticity will emerge through dedication and exploration.

As you begin producing your own work, how do you define creative control? What kind of stories are you most compelled to protect and bring to life under your own banner?

Creative control, to me, is the ability to safeguard the soul of a story—from its emotional truth to its aesthetic language—without dilution or compromise. It’s not about micromanaging every detail, but about ensuring that the core intention, the heartbeat of the piece, remains intact through every phase of its evolution. It’s the authority to say “this matters” and the responsibility to honor that conviction, even when it’s inconvenient or unpopular. The stories I feel most compelled to protect and bring to life are those that wrestle with faith—not necessarily religious faith, but the kind that asks: What do we believe in when everything falls apart? What do we hold onto when the world goes quiet? These are stories of quiet endurance, of spiritual reckoning, of characters who are cracked open and remade—not by spectacle, but by intimacy, by grace, by the slow burn of transformation. After wrapping Somewhere In Montana, I received similar feedback from many locals about “how important it was to see our little corner of the world seen.” That notion has become part of my vision for the stories I want to tell—those that give a voice to the voiceless and shine a light on pockets of our society that deserve to be seen. From that, perhaps we can discover ways to be less divisive and dissonant in our society, finding connection through shared visibility and understanding. I’m drawn to narratives that live in the tension between discipline and surrender. Stories where the body remembers what the mind forgets. Where silence speaks louder than dialogue. Where the process of becoming is messy, sacred, and deeply human. Under my own banner, I want to create work that doesn’t chase visibility, but invites presence. That doesn’t perform emotion, but earns it. That doesn’t resolve neatly, but lingers—like a prayer, or a bruise.

Hollywood can be a tough environment for authenticity. Have there been moments when you’ve had to fight to preserve your sense of integrity — as a person and as an artist?

Absolutely. Hollywood, for all its brilliance, can be a place where the pressure to fit a mold — to be marketable, palatable, or easily categorized — is relentless. I’ve had moments where I’ve had to choose between what felt authentic and what felt expedient. Whether it was turning down roles that didn’t align with my values, resisting the urge to curate a persona for visibility, or simply staying committed to the slow, often invisible work of craft — each choice was a quiet act of defiance.For the role of Fabian, I took the risk to play him “big” because I felt him big — I felt him honestly and truthfully, but I felt him big. With adopting feedback from fellow actors and teachers, I was able to give myself permission to make bold choices unapologetically because to my core I felt the role demanded it, especially in relation to the stoicism and contrasting energy from Graham McTavish.

You hold a 4th-degree black belt in Karate. That’s an intense commitment. What parallels do you see between the ritual of martial training and the daily grind of acting in Los Angeles?

Holding a 4th-degree black belt in Karate has shaped my approach to acting in profound ways. Both disciplines demand a reverence for repetition—not as drudgery, but as a path to presence. In the dojo, we drill kata until the body remembers what the mind forgets. On set or in rehearsal, the same principle applies: you return to the scene, again and again, not to perfect it, but to discover something truer each time. That ritual of showing up, of refining through sweat and silence, builds a kind of embodied faith—one that doesn’t rely on external validation. My experience with Okinawan Shorin Ryu and visiting Okinawa, known for having the longest lifespan in the world, was eye-opening. It revealed to me the true art within the martial art—a depth and spirit that transcends mere technique. This practice, which my father has taught with immense love at the Front Royal Karate Club for decades, has created a family that has always been an earth-shattering entity in my life, one I am deeply grateful for. In Los Angeles, where the pace is relentless and the outcomes uncertain, martial training has taught me to anchor myself in process. A black belt isn’t a finish line—it’s a reminder that mastery is a lifelong practice. Acting, like Karate, requires discipline, humility, and the ability to stay grounded in the face of rejection or praise. Both are crafts of presence, where the body becomes the instrument of expression, and the real work happens in the quiet, unseen hours. That’s where transformation lives.

9. When audiences see you on screen, they might not realize how much of your journey has been self-made — from training to self-funded projects. What’s one chapter of your story that people rarely ask about, but should?

One chapter that rarely gets asked about—but shaped everything—is the stretch of time when I trained alone, outside any formal institution, after my initial studies in New York. No stage, no camera, no audience. Just me, a script, and the discipline of repetition. I’d wake, run lines while moving through martial arts drills, then spend hours refining micro-expressions in the mirror—how grief flickers before it’s swallowed, how faith lives in the eyes before the words arrive. I wasn’t preparing for a role. I was preparing for the kind of artist I wanted to be: someone who could carry silence, who could make stillness speak.That chapter taught me that mastery isn’t glamorous. It’s devotional. And it’s often invisible. But it’s the reason I can walk onto a set now and trust that my body, my breath, and my belief will meet the moment.Before that, there was the struggle of bartending until 5 a.m. in New York City, the relentless nights filled with clinking glasses and the hum of conversations, all while holding onto a dream. Then came the leap to Los Angeles, jobless but determined, taking on whatever came my way—cleaning houses, painting walls, yard work—each task a stepping stone, each day a testament to resilience.I am deeply proud that every job, every challenge, has been in service of a greater purpose: to craft stories and characters that resonate, that meet the moment, and that urge people to reflect and embrace their shared humanity.

If your life right now were a film, what would the final frame look like — and what would you want it to say about where you’re headed next?

The final frame would be quiet, deliberate, and full of tension — not the kind that breaks, but the kind that holds. A single figure stands at the edge of a rehearsal space, barefoot, sweat-dampened, still breathing from the last run-through. The light is low, golden, catching the curve of their back as they face an empty stage. No applause. No audience. Just the silence of process.That frame wouldn’t signal arrival. It would signal readiness. A life built on repetition, risk, and reverence — now poised to step into something deeper. Not fame. Not certainty. But a new act where mastery meets mystery, and the work begins again.

His journey is proof that artistry is not born from speed, luck, or the noise of visibility. It’s carved from ritual—the repetition of breathwork, backstory, kata, character study, and the quiet hours no one ever sees. In a culture obsessed with the finish line, he is committed to the path itself: the discipline, the faith, the spiritual reckoning that happens long before the camera rolls. As he moves deeper into producing, storytelling, and the evolving landscape of his craft, one truth is clear: he is not chasing the spotlight. He is building something that lasts—work that lingers, work that listens, work rooted in the slow, sacred art of becoming.

Photos By Mariposa Pictures