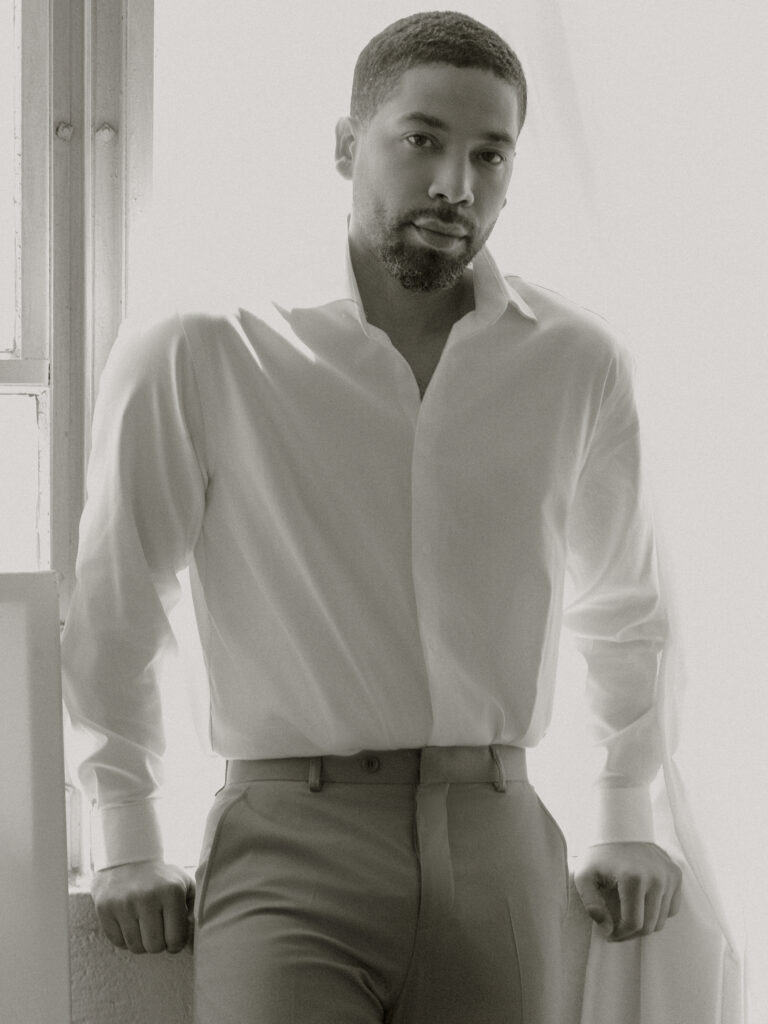

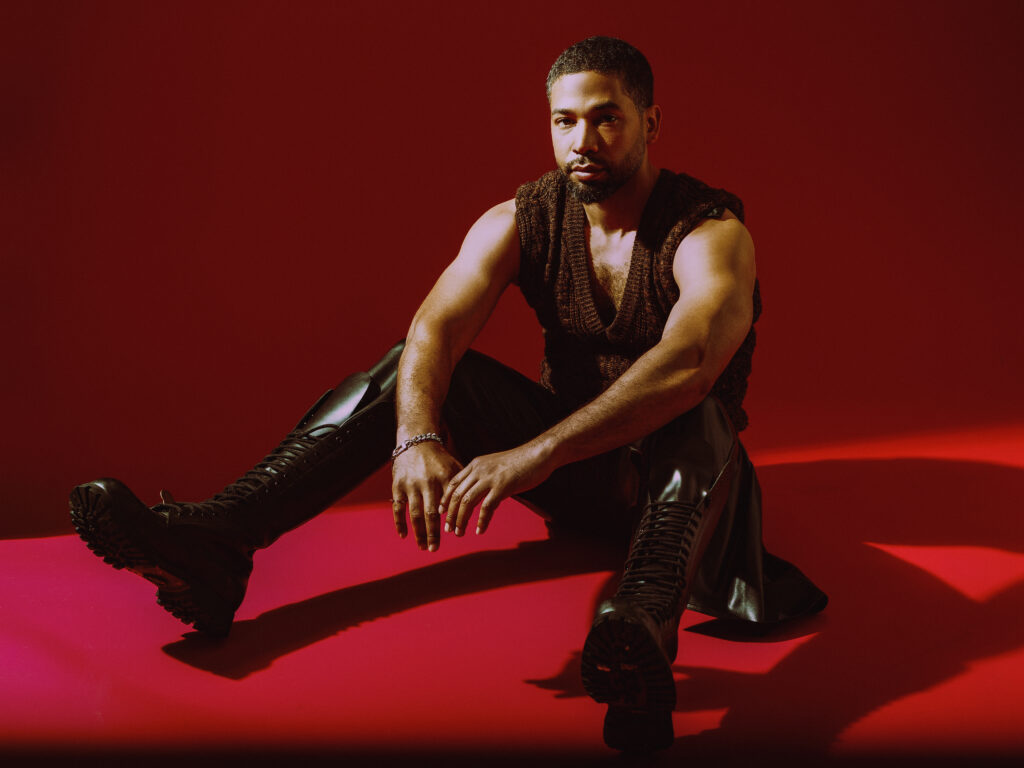

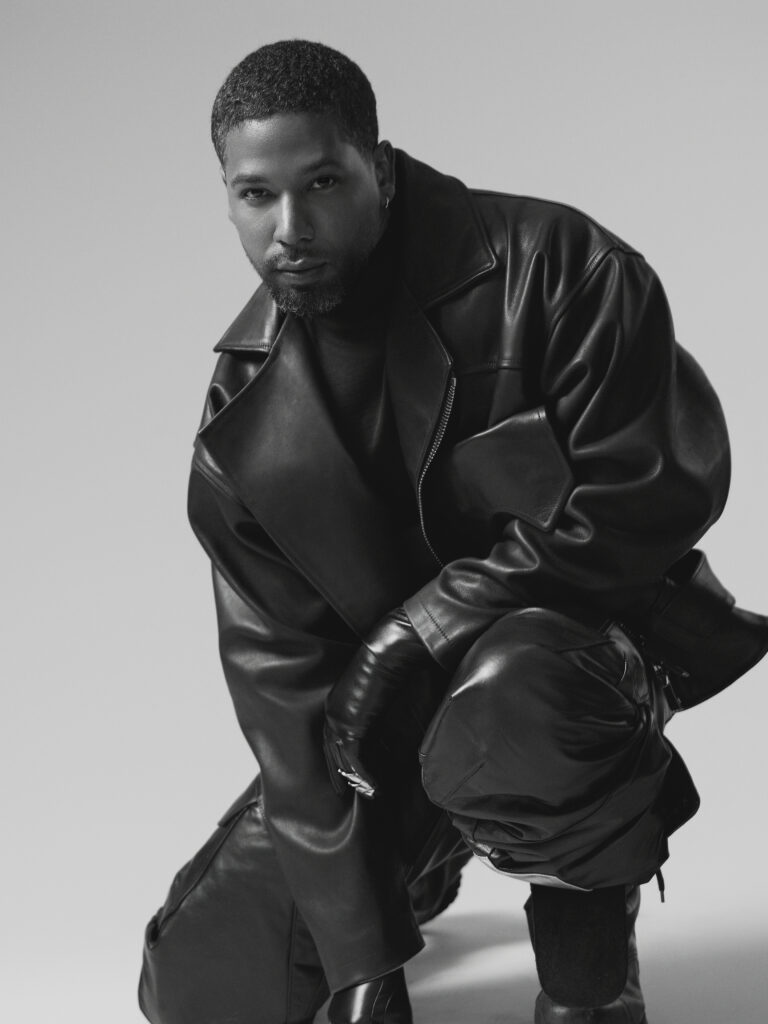

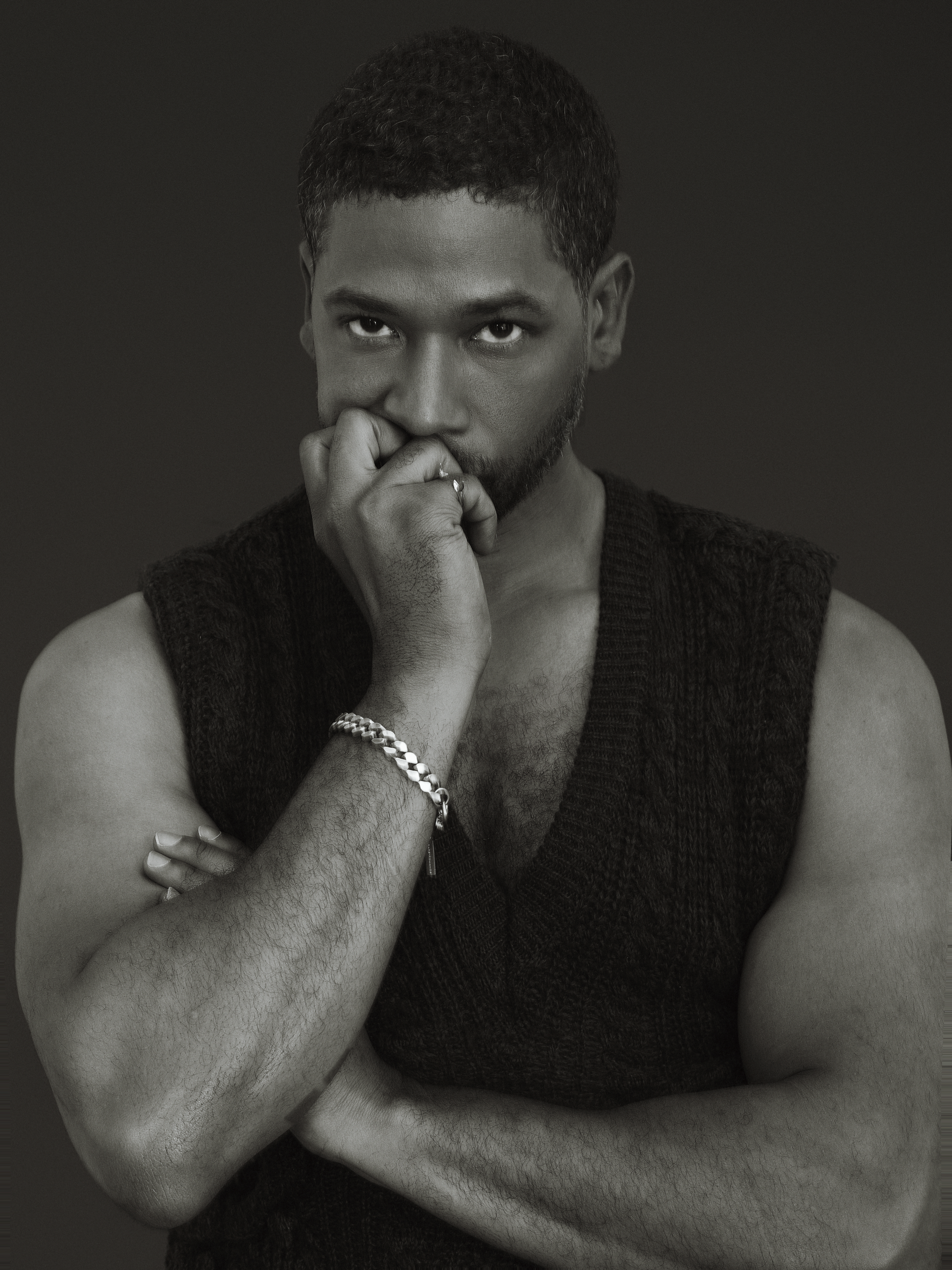

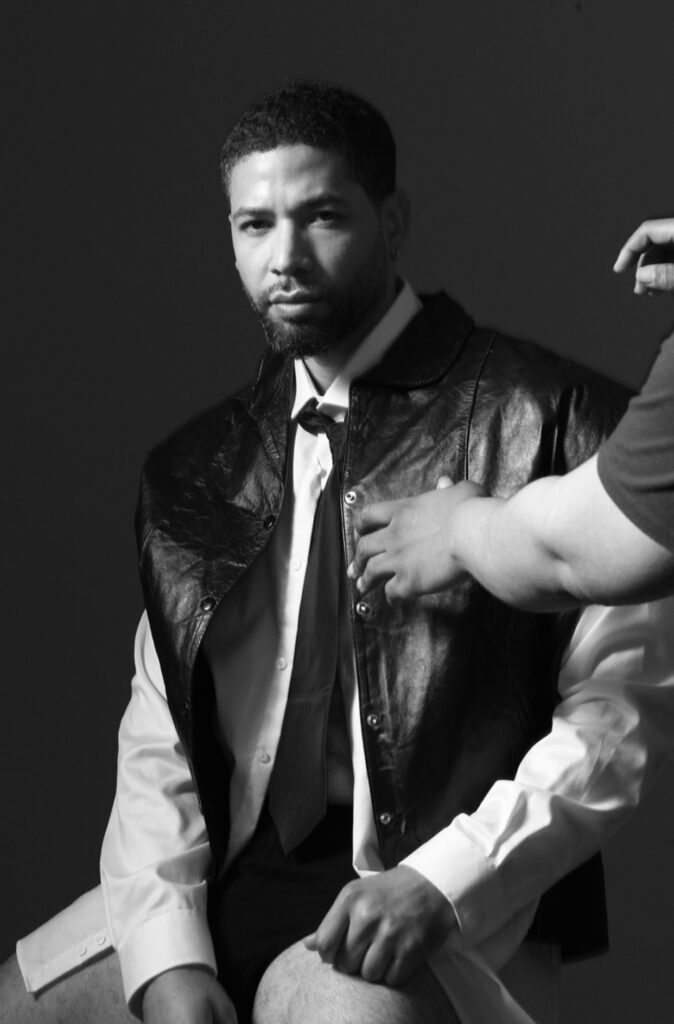

London Solitude, Global Voice: The Reinvention of Jussie Smollett

Jussie Smollett has always treated art as both sanctuary and megaphone—whether through music, film, or activism. Now, after relocating to London, he’s discovered a cadence that feels more attuned to his spirit. The city’s slower rhythm, its space for solitude, and its distance from the constant churn of Los Angeles and Chicago have given him a clearer channel to hear himself again. “I feel calmer here,” he admits. That calm has already led to finishing a new screenplay, writing fresh melodies, and shaping his latest music with an openness that thrives on time and stillness.

You’ve relocated to London—how has that shift in city, cadence, and solitude changed the way you write melodies and design your vocal arrangements? What did you have to unlearn from the LA/Chicago grind to hear yourself clearly again?

JS: That’s such a great question. I feel a bit calmer here. I’m sure anyone who was born and raised here would think I’m crazy for saying this, but the pace is a bit slower, and that mellows me and allows me to stop and just breathe. As far as my work and creating… I’ve finished the screenplay for my next film here and have already started writing new music. I’m inspired. When I’m calm… it allows for beautiful creativity to float in. When I’m constantly consumed with what’s directly around me, it can lead to distractions. There’s a level of solitude I crave. I get that here. And that’s not to say that the US doesn’t give that because my whole family’s there, but it’s nice to see and try out different sides of the coin… or world.

The title track of Break Out dropped on August 12, 2025. What are three specific “risks” you took sonically on this album—choices you might’ve talked yourself out of five years ago—and what finally freed you to keep them in the final mix?

JS: I did what I wanted to do with this album. I’ve been fortunate to understand myself as an artist, but there were plenty of times when I felt stifled or controlled by a system in place who made up what was expected of me. As a solo artist and as the artist I was portraying at the time. It was a blessing because of the opportunity it presented and made sense then for the project we were mainly on, but now there’s a freedom that feels like back in the day when I was a happy, indie artist. We wanted to make a timeless album with the majority of live music. We took our time. If something didn’t work… we had time to fix and change it. I gave myself time and space to jus be.

Your early world tour proceeds went to charity. Looking back now, do you feel artists should treat philanthropy as a side contribution or as a central part of their brand DNA? And what would it look like if the music industry held itself accountable for measurable social impact the same way it does for chart positions?

JS: Whew! Oh, you’re coming with the real questions! For me, that’s just how I was raised. With every single thing you do, you think of the way in which you can be of service to help others. It’s not for show. It’s not to sell extra tickets or gain admiration. It’s just the world in which we should live. With that said, I’m not one to expect others to do the same. We are all different with different callings. I would say that as far as executives go… hell yes. There’s a responsibility that the big money folks should have to not only be concerned with what’s happening in the world outside but also with the artists inside their building.

Empire’s Jamal Lyon was a watershed for audiences who rarely saw themselves centered with that nuance. If you could write a 2025 epilogue for Jamal—new technologies, new politics, new loves—what conversation do you think he’d be leading now?

JS: Jamal is still somewhere exiled in London with his husband. I’ll look for him and let you know what the brother is up to. (Laughs). I’m not sure where Jamal would be now. I was always forcing him to be more political and involved with issues that not only affected him and his family but the outside world. But Jamal grew up very differently than I did. He was privileged in a way that I can’t even fathom, so our priorities have always been different. I hope he’s well wherever he is haha.

You embodied Langston Hughes in Marshall and worked opposite Chadwick Boseman—artists who treated craft as civic work. What’s one lesson from that set you still apply when deciding whether a role or lyric actually moves culture, not just charts?

JS: Being able to portray Langston Hughes is still one of the great prides of my life. I’ve looked to his wordplay and genius since I was seven years old. Between Chadwick and Reginald Hudlin, it was a study of the greats. Chad was effortless, but you could tell how hard he studied and worked. He was so kind and generous with his time, even outside and after work was done. Reggie is a legend and is so collaborative. I’ll never forget the short but impactful time of working with them both.

You wrote, directed, produced, and starred in The Lost Holliday. Wearing all four hats, what is the one element you will never outsource again because only you can protect it on set? And what did collaborating with Vivica A. Fox unlock that surprised you?

JS: I need an extra day to film! Haha. We shot my last two films in 11 days each. It’s insane! I’m so nosey about everything. And it’s hard to hand things over because I’m so specific but I will need at least 13 days for the next one. Vivica is such a pro. It just makes you want to be top notch in every way. She knows her stuff and understood the value of time so she was beyond prepared. If I could have a Vivica to get everyone together each project, I would.

B-Boy Blues earned a Fan Favourite at ABFF and a GLAAD nomination. When you’re staging intimacy and Black love, what’s your ethic behind the camera—consent choreography, lighting, lens choice—that keeps vulnerability from being consumed as spectacle?

JS: oh my gosh absolutely. We had an intimacy coordinator and choreographed it before the actors even stepped in. My cinematographer, Jody Williams, and I planned in depth how it would be shot, what body parts you’d see vs what was implied, etc. I’ve done love scenes before and it’s just not normal. There’s nothing sexy about it but here you are having to sell it. My number 1,2,3,4 & 5 priority is that the actor is as comfortable as humanly possible because they have to walk away feeling respected and valued. I’m an actors Director. Period.

8. Without re-litigating the past, the 2019 Chicago incident and its aftermath reshaped the public square around you. What does repair look like in your life now—one concrete practice you’ve adopted with collaborators, fans, or community—and how do you measure trust over time?

JS: I don’t know that I’m trying to repair as much as I’m simply trying to live and love. I don’t want to be a divisive figure. I want to bring people together. That’s always been the mission. Always will be and I want for people to know that. I’ve been through it, yes.. But I tell myself often, because I’m human and I can get in my feelings and even self pity sometimes. I’m not the only one who’s been put through the wringer. And I’m blessed to have the resources and platform I have. As far as trust goes… I used to trust first and start to bend once finding out someone is not who they claimed to be. Now? Baby you have to prove to me because we aren’t giving away trust tickets for free anymore.

9. You’ve supported organizations from The Black AIDS Institute to the Chicago Torture Justice Center. If you had one year to move a needle on a single policy or budget line these groups fight for, what’s the winnable goal—and how would your platform help get it over the line?

JS: I would make healthcare free for everyone, with a particular focus on women and children. Affordable healthcare supports both mental and physical wellbeing, and women deserve access at every stage, from adolescence through adulthood, whether or not they choose to have children, all the way through menopause and beyond. Women carry so much of the heavy lifting in our society: nurturing, caring, and raising the next generation. Their strength and resilience keep communities thriving, and it is essential that their health and wellbeing are fully supported and prioritized at every step of their journey.

The music economy is being rewritten by algorithms and AI. Where do you personally draw the line on voice cloning, stem licensing, and synthetic collabs? Would you ever open-source your stems to invite community remixes—or is sovereignty the point?

JS: I think people should do what they want creatively. Just please leave my voice out of it. I remember a time when autotune was thought to be the worst thing ever. Now mostly everyone uses it as a tool of convenience. But we as artists should have full control or our vocal just as we should have our likeness of any kind. That’s common sense and basic respect. Don’t take my choices away.

Public scrutiny can compress imagination. What boundary or ritual—something tangible, not abstract—protects your creative state on days when the noise is loud but the work still has to be honest?

JS: My Mothers voice. Even when she’s joking or even mad… it makes me know what’s important and what’s not so I can silence those voices.

Smollett’s journey has never been linear—at times turbulent, at times triumphant—but always deeply human. In London, he’s writing from a place of clarity and solitude, but also of renewed purpose: to connect, to heal, and to remind audiences that vulnerability can be its own form of resistance. Whether through a lyric, a lens, or a line of dialogue, his work insists that art should move culture as much as it entertains. And for Smollett, that mission has never felt more urgent.

Photography Ace Amir

Interview Kyra Greene

Barber Paris Wagner

Stylist Brendon Alexander

Assistant Stylist Jailyne Navarro