Civil War and the Cost of Choosing Sides

By Kyra Greene

When Marvel quietly released the Civil War Facsimile Edition, it wasn’t framed as a cultural event. There were no sweeping claims about restoration or modernization, no promises of a “definitive” version. Instead, the release functioned more like an archival gesture—one that asked readers to encounter Civil War exactly as it existed when it first split the Marvel Universe in 2006. No edits. No corrections. No recalibration for modern sensibilities. Just the work, preserved in its original state.

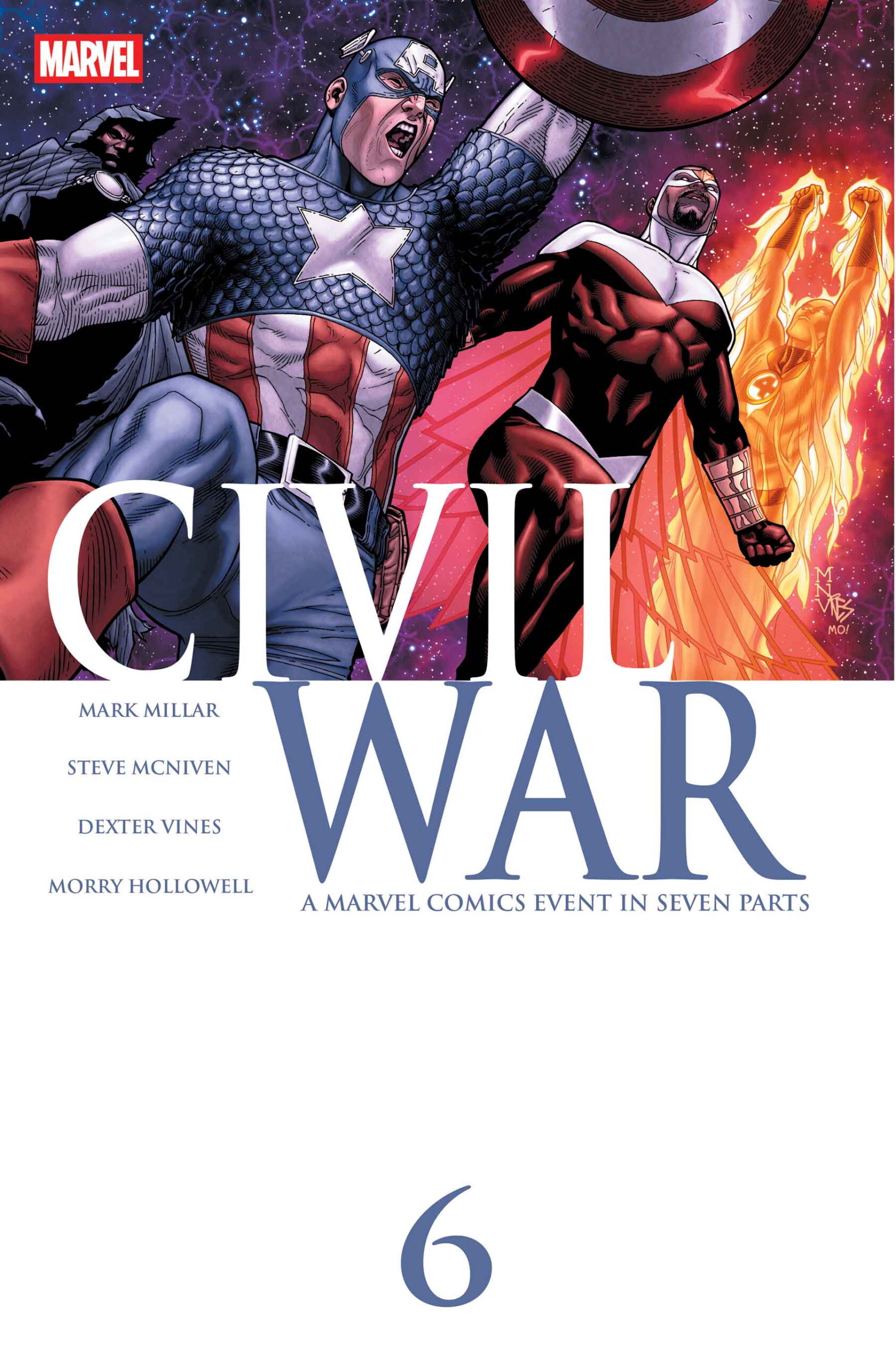

This matters because Civil War was never a subtle comic, and it was never built to age quietly. Written by Mark Millar with artwork by Steve McNiven, the series used the Superhuman Registration Act as an unmistakably political lens, foregrounding questions of surveillance, state power, personal liberty, and collective fear. The story didn’t disguise its intent through metaphor; it placed its ideology directly on the page, forcing characters—and readers—to take positions without the comfort of moral clarity. Captain America’s defiance and Iron Man’s compliance were not framed as hero versus villain but as incompatible philosophies, each rooted in genuine conviction and equally capable of causing harm.

The facsimile format preserves not just the narrative but the experience of encountering those ideas in real time. The original coloring palette, the mid-2000s Marvel lettering, the pacing dictated by single-issue cliffhangers—all of it remains intact. Even the advertisements, often stripped from later collections, are present here, situating the comic firmly within its original cultural and economic context. These ads are not distractions; they are timestamps, anchoring the story to a specific media ecosystem and reminding readers how Civil War was consumed, debated, and argued over month by month rather than binged in a single sitting.

In an era where reprints are routinely “improved,” the restraint of the facsimile edition feels deliberate. There is no attempt to sand down the rough edges or offer retrospective commentary. The book doesn’t apologize for its politics or contextualize them through modern framing. That refusal is part of its power. Reading Civil War now, the parallels to contemporary debates around accountability, public safety, and civil liberties land with an almost uncomfortable clarity. The facsimile edition doesn’t guide the reader toward conclusions; it simply presents the work as it was and trusts that its arguments are strong enough to withstand time.

This trust distinguishes the facsimile from omnibuses, trade paperbacks, and digital editions. Those formats prioritize convenience and completeness, but they inevitably flatten the original rhythm of the story. Civil War was designed to create tension through delay, to allow uncertainty to fester between issues, and to let public opinion—both inside and outside the comic—shift in response. By restoring that structure, the facsimile reintroduces a sense of urgency and fragmentation that is central to the story’s impact.

Long before the Marvel Cinematic Universe adapted Civil War into a controlled spectacle, the comic was raw, divisive, and intentionally unsettling. Heroes imprisoned heroes. Alliances collapsed. Trust became a liability. The facsimile edition restores that discomfort without dilution. It reframes Civil War not as a nostalgic milestone or franchise cornerstone, but as a primary document from a moment when superhero comics were willing to antagonize their audience and refuse easy answers.

In preserving Civil War exactly as it was, Marvel has inadvertently made a statement about why the story still resonates. The questions it raised were never resolved—they were postponed. The facsimile edition brings them back into circulation, unchanged, and asks readers to confront them again. Not as mythology. Not as cinematic canon. But as a printed argument that remains unresolved, and therefore, still urgent.