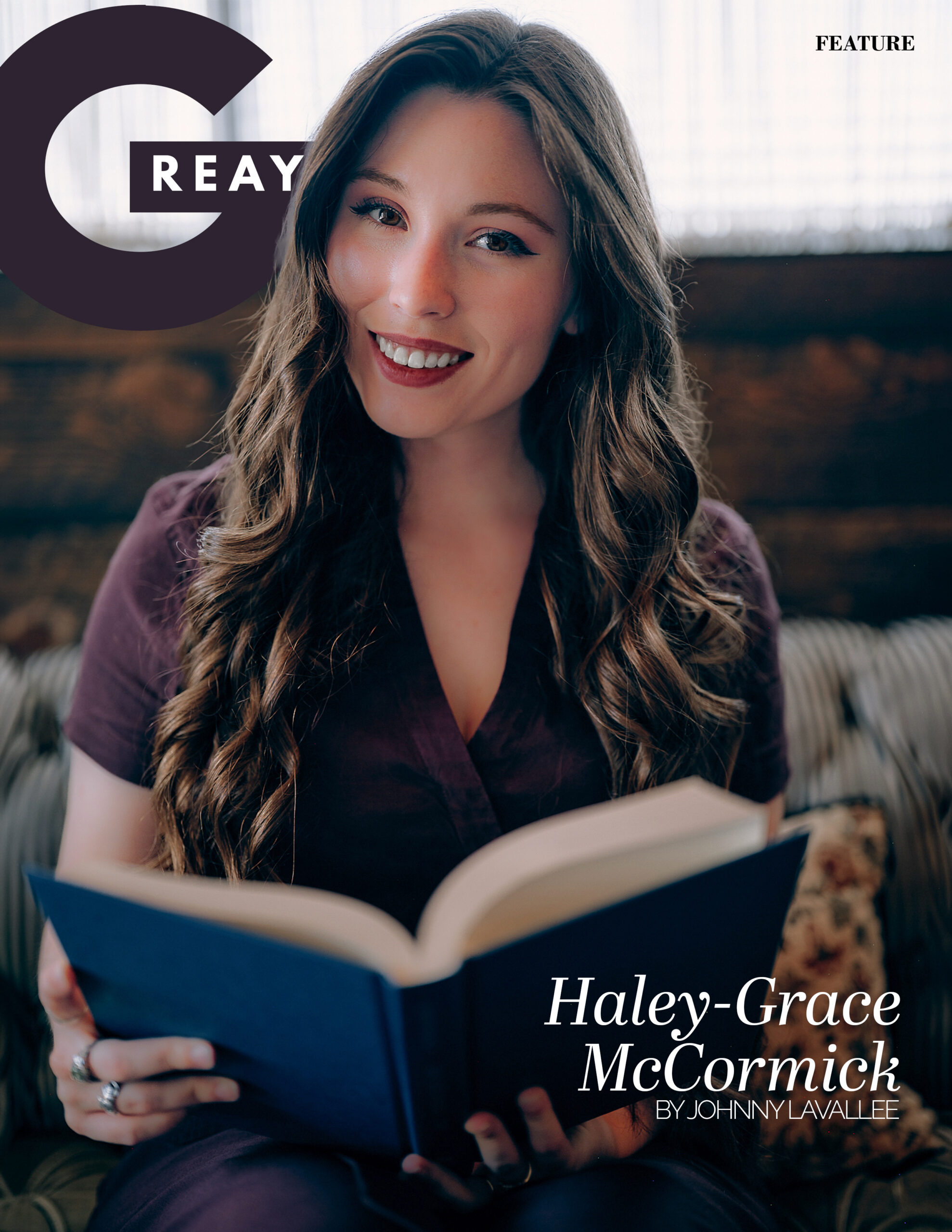

Haley-Grace McCormick Writes Against the Clock

By Norma Gillerson

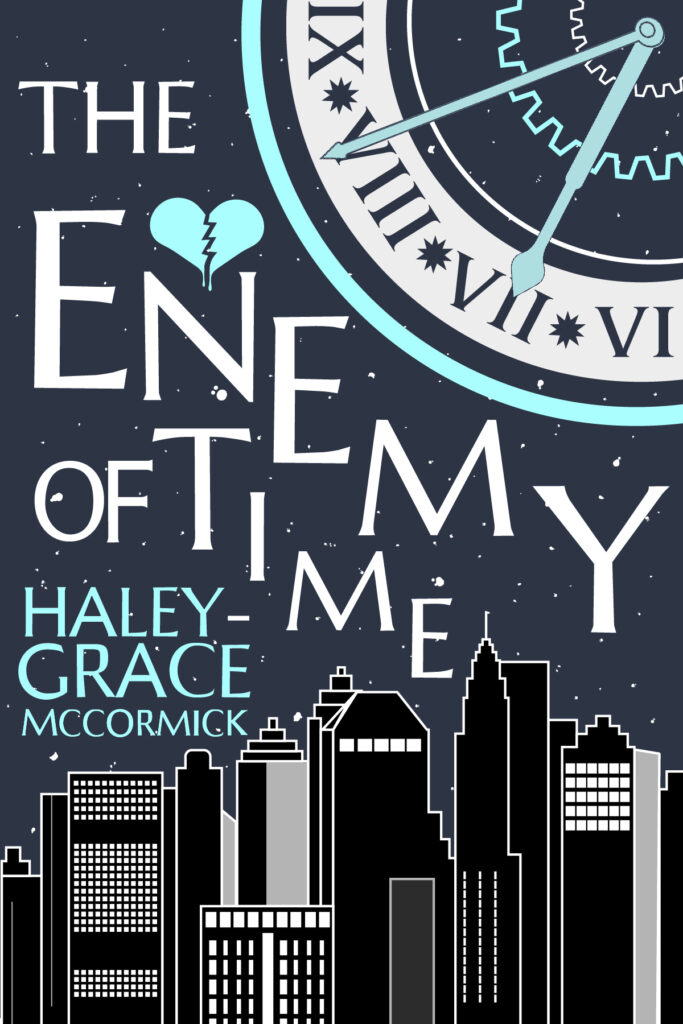

There’s a version of Haley-Grace McCormick that lives online—curated, articulate, and fluent in the visual language of modern storytelling. But beneath the clips, annotations, and aesthetic frames is a quieter rhythm: one defined by stillness, attention, and a lifelong devotion to stories not as content, but as refuge. As she steps into authorship with her debut novel The Enemy of Time, McCormick isn’t rushing to define herself by titles. She’s more interested in the moments that linger—the ones that shape us long before we learn how to name them.

When you strip away the labels—author, content creator, actor—who is Haley-Grace in the quiet moments no one films or reads about?

I’m actually exactly what you see online. I’m usually reading, or watching a movie, or deep into a TV show. My life really does revolve around stories and storytelling. If I’m not consuming them, I’m out with friends trying to experience as much as I can in the time I have.

I care a lot about enjoying the small moments in a day. Sometimes that looks like watching a movie I love with my friends or my parents. I love going to the movie theater—not just for the film, but for the whole experience around it: the popcorn, the conversations, sitting in the dark together, and seeing where the movie takes us.

I think the biggest difference is that I’m quieter than I appear online. I like to take things in. I pay attention. I try to be present for moments as they’re happening instead of rushing through them. In a lot of ways, that’s where my love for stories comes from—learning how to sit with a moment long enough to really feel it.

The Enemy of Time lives at the intersection of nostalgia, regret, and first love. What personal memory do you feel humming underneath the story, even if it never appears on the page?

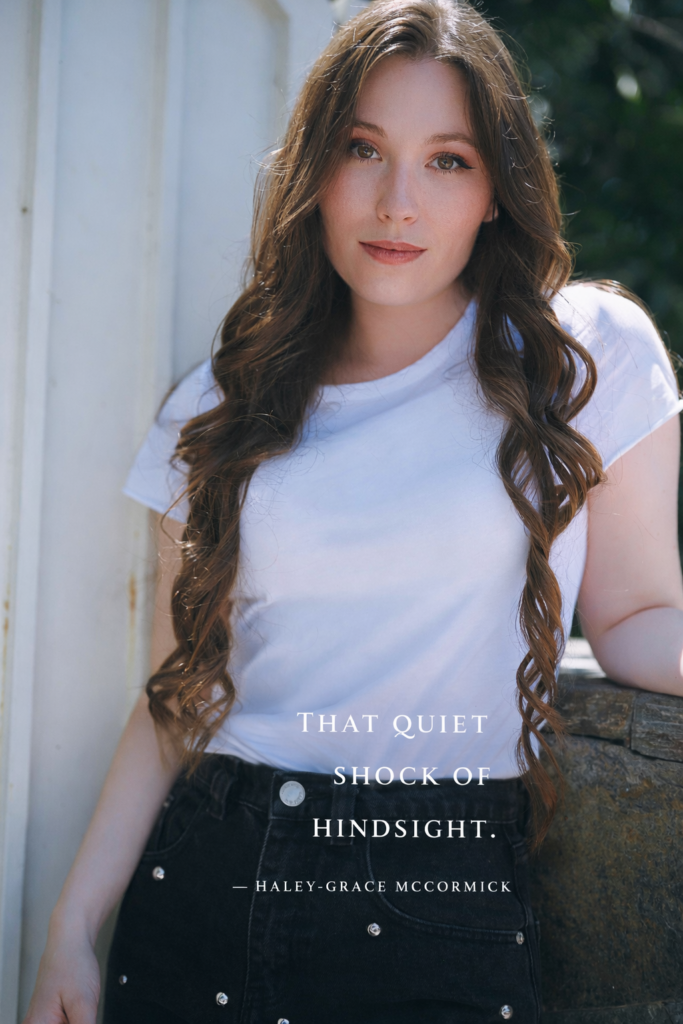

It’s less a single memory and more a feeling I’ve carried for a long time—the moment you look back and realize something mattered more than you understood while it was happening. That quiet shock of hindsight. Of knowing you were living inside something formative without having the language for it yet.

First love does that. It teaches you how deeply you’re capable of feeling, even if it doesn’t last forever. That awareness hums beneath the entire book. It’s not about recreating a specific relationship, but about honoring the way certain moments stay with us long after they’re supposed to be over.

You’ve described yourself as a dyslexic writer and fiction fanatic. How has that rewritten your idea of what intelligence and creativity are supposed to look like?

For a long time, I thought intelligence meant speed—how quickly you could read, respond, or articulate an idea. Dyslexia forced me to move through the world differently, whether I wanted to or not. Over time, I realized that slowness wasn’t a lack of intelligence—it was a different relationship to it.

Creativity, for me, comes from lingering. From revisiting ideas. From understanding things emotionally before I can put them into words. Writing taught me that intelligence doesn’t have one shape and creativity doesn’t have one pace. Sometimes depth comes from taking the long way around.

Your life unfolds in fragments—15-second clips, paragraphs, annotations, drafts. How has living inside an algorithm changed the way you think about time on the page?

Living inside an algorithm has made me very aware of how compressed time can feel. Online, everything is designed for immediacy—what can be understood quickly, what can be consumed fast. Writing a novel became a quiet resistance to that pace.

On the page, I let moments breathe. I let memory interrupt the present. I allow silence and stillness. If social media taught me how quickly moments pass, writing taught me how to slow them down and ask what they’re actually made of.

When you revisit your own past, what are you still trying to make peace with?

I’m still making peace with the version of myself who didn’t yet feel allowed to want certain things. Who stayed quiet about what mattered most because she wasn’t sure she was supposed to choose it. That uncertainty shaped how I moved through friendships, love, and creativity.

Now, when I revisit that past, I don’t try to rewrite it. I let it exist as it was. It reminds me that growth doesn’t come from finding the right answer, but from allowing yourself to learn that there isn’t one.

If you could freeze one frame from The Enemy of Time and hang it in a gallery, which moment would it be?

It would be Jamie and Alex’s first kiss. There’s something so innocent about a first kiss, and yet it’s one of those moments that stays with you forever. It becomes a timestamp in your life.

That moment holds anxiety, wonder, and fear all at once. You learn who they are in that instant—how they approach vulnerability and what they’re willing to risk. Long after it passes, it continues to shape them, which is exactly what first love tends to do.

Where do you feel the most like an artist, and where do you feel the most like a performer?

I feel the most like an artist very early in the morning, usually after way too much coffee, when I couldn’t sleep because my brain wouldn’t stop thinking about a character or a line that suddenly feels urgent. That quiet, slightly unhinged space is where the real work happens.

I feel the most like a performer when I’m communicating online—talking with people who love stories as deeply as I do. There’s joy in that exchange. Both matter. They just ask for different parts of me.

If your future self could send one sentence to the Haley-Grace writing this debut—no context, no caption—what would it say?

Say it now. Do it now. Love now. Because time doesn’t guarantee you another moment.

What makes Haley-Grace McCormick compelling isn’t speed, scale, or spectacle—it’s her willingness to linger. In an era trained to rush past feeling, The Enemy of Time insists on stillness, on noticing what’s already slipping away. Her debut doesn’t chase urgency; it interrogates it. And in doing so, McCormick joins a quieter lineage of storytellers—those who understand that the most lasting narratives aren’t built to keep up with time, but to sit with it long enough to be changed.

Photography – Johnny LaVallee @lavellee.l.a

POST COMMENT